Some tests are fast. You can run 1000s of them in seconds. These are the tests that are the heart and soul of TDD, so you run them every chance you get.

There are other tests that aren’t so fast. Because they’re slow, you don’t want to run them often. You’ve got better things to do than to sit and wait for test results to come through.

Unfortunately, the less you run your slow tests, the less valuable they are. By moving your slow test runs off your machine and running them every time you make a change, you can make sure you’re getting the most value out of your slow tests.

This is one reason why I think CI is so important. At every job I’ve had, setting up a CI is one of the first things I’ve done, and now that Jenkins has gotten a little more sophisticated with its “Pipelines,” I thought I should document how I set things up somewhere.

My hope is that if my future self has a different job that requires him to setup Jenkins for Android Testing, he’ll find this useful. If your current self needs to setup Jenkins so that you can maximize the value of your slow tests, I hope you find this useful too.

The Jenkinsfile

1node('android') {

2 step([$class: 'StashNotifier'])

3 checkout scm

4 stage('Build') {

5 try {

6 sh './gradlew --refresh-dependencies clean assemble'

7 lock('emulator') {

8 sh './gradlew connectedCheck'

9 }

10 currentBuild.result = 'SUCCESS'

11 } catch(error) {

12 slackSend channel: '#build-failures', color: 'bad', message: "This build is broken ${env.BUILD_URL}", token: 'XXXXXXXXXXX'

13 currentBuild.result = 'FAILURE'

14 } finally {

15 junit '**/test-results/**/*.xml'

16 }

17 }

18 stage('Archive') {

19 archiveArtifacts 'app/build/outputs/apk/*'

20 }

21 step([$class: 'StashNotifier'])

22}There’s a couple of lines worth highlighting here.

1 node('android')

A node is a computer that can execute a Jenkins job. A single Jenkins “master” server can queue up jobs for many nodes, so you can run as many jobs as you have machines simultaneously.1

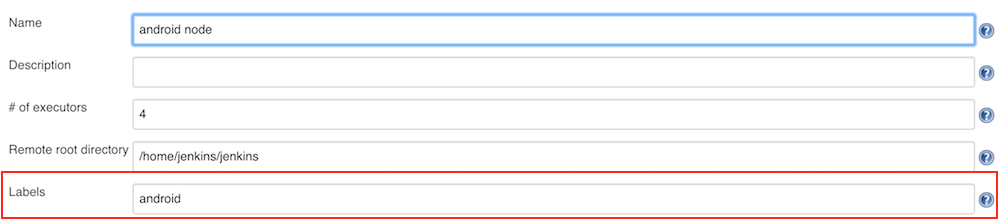

What’s interesting about this line is the parameter that node() takes. The value of this parameter is a “label,” which is a way of telling Jenkins which types of nodes can run this job. With this line, I’m saying: “Only run this job on nodes that have the label ‘android’.” When managing your nodes through the Jenkins UI, you can specify which labels your node has, thereby limiting the execution of your jobs to particular nodes:

OSX machines are more expensive than the linux machines that can run our Android builds, so we currently use labels to ensure that android build jobs aren’t tying up the (more expensive) OSX machines.

2 step([$class: 'StashNotifier'])

Prs can be gated by your Jenkins build. In other words, you can set things up so that no one can merge a pr with failing tests or lint violations. This pr gating is made possible by this step and the Stash Notifier plugin that exposes it.

If someone can merge broken code into master in spite of failing tests, those tests aren’t as valuable as they could be.

Flaky tests are made especially painful by pr gating based on test results. I think this is a good thing, as flaky tests can be a subtle poison to your testing suite. By making their poison more explicitly felt through pr gates, we’ll be more motivated to fix them or delete them. Better that, then for people to start ignoring test results.

6 sh './gradlew --refresh-dependencies clean assemble'

One way of thinking about a CI server is that it continuously runs what we might call “the integration test,” which we might express as follows:

Given a working code base

When new code is merged in

Then we still have a working code base“working code base” here is fleshed out by the specific steps in a Jenkinsfile, but is often defined as follows:

“A working code base builds from a fresh checkout and all the tests pass.”

The “fresh checkout” bit of the definition is often necessary to avoid the proverbial “but it builds on my machine” excuse.

Since developers and their computers are not invincible, a particular developer’s machine is not the source of truth for whether a build is broken. The CI server should be that source of truth, as it tells us whether its possible for a new developer to build a project on a new machine.

This is why --refresh-dependencies and clean are included in this line. --refresh-dependencies is particularly important if you’re using SNAPSHOT dependencies, as I’ve run into cases where the build appears to be fine but is actually broken, and I couldn’t tell because the CI server was using a cached SNAPSHOT dependency.

7 lock('emulator') {}

Suppose you have a quad-core node that builds Android jobs. Nodes often have an executor for each of their cores. This allows Jenkins to take full advantage of multi-core machines, as it can run a job for each core on a machine. A quad-core node, for example, could run 4 jobs simultaneously.

Now, suppose that two jobs for two branches get kicked off simultaneously. If there’s only one emulator available on a node, you could have a problem: one test run could try to access the emulator while the other is using it, thereby causing failures. Locks solve this problem.

This line of code grabs a lock on a resource labeled as “emulator,” and retains that lock until the code running inside its block has been completed. Any other jobs that try to run tests against the emulator while the lock is held by a particular job will have to wait, which ensures that you can take full advantage of the parallelism gained by adding additional nodes and executors.

12 slackSend channel: '#failures', message: "Broken build ${env.BUILD_URL}"

If a build on the CI passes, great. That should be the status quo. With all the noise in our emails and slack channels, we don’t need a notification that says, in effect, “everything is still working just fine.” Any source of information that provides us with useless information MOST of the time seems likely to be a source of information that we’ll pay less attention to over time.

This is why I only post build failures to a slack channel. A broken build is a big deal. Ideally, a developer will investigate a broken build immediately.

When broken builds aren’t investigated immediately, we lose the value of our tests and CI, which are supposed to give us feedback on our code while the changes are still fresh in our mind. It’s much easier to fix broken code immediately than it is to fix it 3+ days later when the changes we’ve made aren’t fresh in our mind.

All that to say, a slack notification seems appropriate for build failures.

Conclusion

I’ll conclude with an exhortation for my future self and for all the selves engaged in the noble struggle of Android dev:

Slugging around in the Jenkins web UI may not be as interesting as writing an elegant Observable cascade for loading data in your Activity, but it’s necessary if you’re going to maximize the value of the tests you’ve already written. Take solace in the fact that you’re efforts are making your team more effective.

Notes:

- Actually, you can run more jobs than this. Each node can have multiple executors, and the folks at Jenkins recommend that you create an executor for each core on the node.