This post is a continuation of my attempt to reproduce my recent DevFest talk in written form.

This post is a continuation of my attempt to reproduce my recent DevFest talk in written form.

Penrose Steps, Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde, and Android Testing

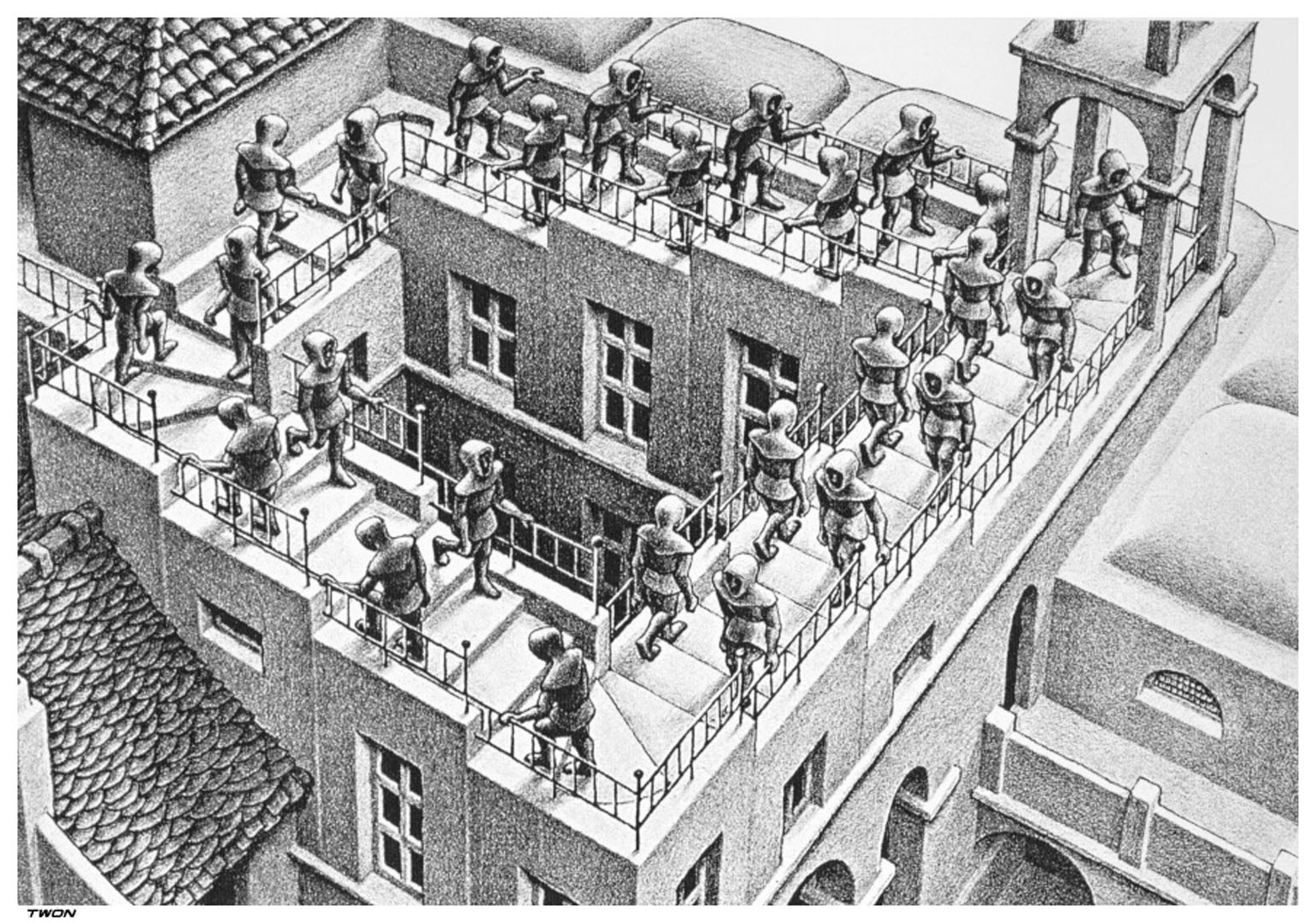

Let’s say you’re sold on the importance of testing. (If not, maybe check out this article.) Let’s say you actually start using the junit dependency that’s been sitting in your build.gradle file and try to write your first test. I suspect that you’re going to find yourself in a kind of “penrose steps situation.”

The penrose steps, shown above, is an impossible structure. Penrose steps cannot exist in 3d space. What’s interesting about the 2d image of penrose steps, however, is that its not immediately obvious that what is being depicted is impossible.

Something similar can happen when we go to start writing tests for our code. We look at our code and we think, “I can totally write tests for this.” Upon further inspection, however, we realize. “Oh wait. This is actually impossible.” This penrose steps experience isn’t limited to Android developers:

Something nearly everyone notices when they try to write tests for existing code is just how poorly suited code is to testing.

– Michael Feathers, Working Effectively with Legacy Code

Testing support for Android has gotten a lot better in the past couple of years, but I think that actually attempting to use the testing tools that are now available for Android has helped us realize that our apps aren’t actually structured in a way that makes testing easy and in some cases, our architectures simply make it impossible to test our code.

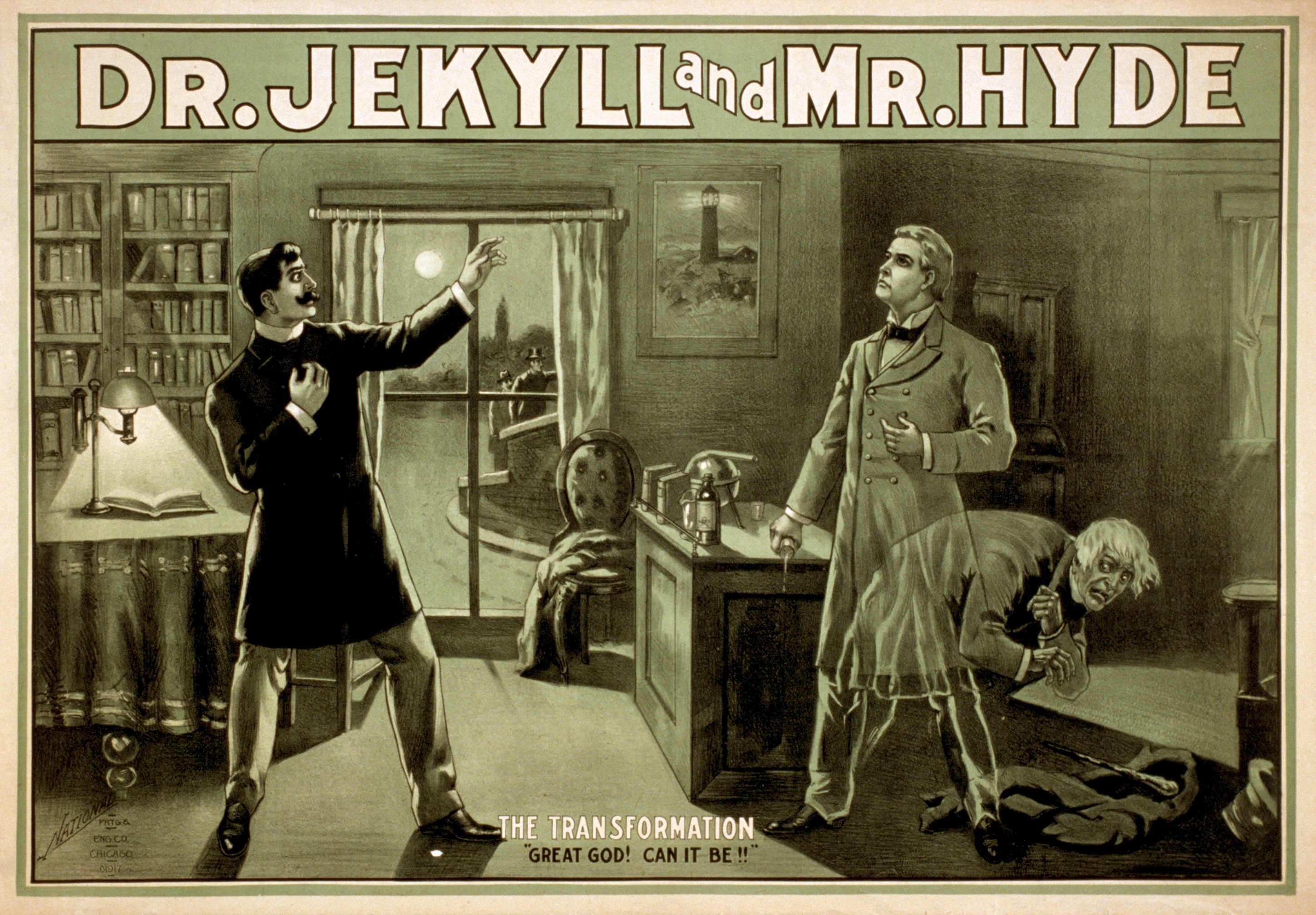

This mismatch between our good intentions and our poorly structured apps can lead us to a kind of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde situation.

Dr. Jekyll was a good dude, but he was messing with something he didn’t understand and that led him to transform into Mr. Hyde, the guy that does unspeakable things. Similarly, developers who want to test their code have good intentions, but if they don’t understand what makes code testable, they can do unspeakably (terrible) things to a codebase.

Case in point: The google 2015 I/O app contains a particularly egregious violation of the principle of single responsibility:1

public class PresenterFragmentImpl extends Fragment

implements Presenter, UpdatableView.UserActionListener,

LoaderManager.LoaderCallbacks<Cursor> {

@Override

public Loader<Cursor> onCreateLoader(int id, Bundle args) {

Loader<Cursor> cursorLoader = createLoader(id, args);

mLoaderIdlingResource.onLoaderStarted(cursorLoader);

return cursorLoader;

}

@Override

public void onLoadFinished(Loader<Cursor> loader,

Cursor data) {

processData(loader, data);

mLoaderIdlingResource.onLoaderFinished(loader);

}

}This code snippet mixes production code and test code. That’s pretty unfortunate.

What Makes Software Testable?

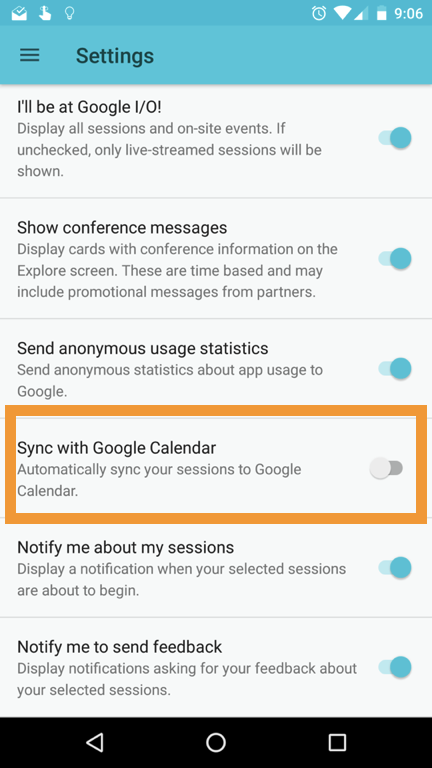

To avoid Penrose steps and Dr. Jekyll scenarios while we’re trying to write tests for our Android apps, its helpful to have an answer to the question, “What makes Software Testable?” This picture suggests a metaphor for thinking about the answer to that question, a metaphor that I stole from Michal Feathers:

If we want to change the appearance of this piece of fabric, we have two options: we could just directly apply whatever changes we want to the pieces of fabric that are joined at the seam. Another option, however, is to undo the seam and replace one piece of fabric with another.

Similarly, when we want to change the behavior of code for testing purposes, we have two options: we can directly apply our changes to the particular source file or we can use what Feather’s calls a “seam” to change the code’s behavior. Here’s how Feathers defines a seam:

A seam is a place where you can alter behavior in your program without editing in that place.

Perhaps the easiest way of fleshing out this concept of a seam to see what it feels like to try to write tests for code that has no seams. Say we wanted to write code for a piece of functionality in the Google I/O app:

This toggle determines whether the google I/O calendar should be synced to the user’s personal calendar. Here’s the code for it:

@Override

public void onSharedPreferenceChanged(SharedPreferences sharedPrefs,

String key) {

if (SettingsUtils.PREF_SYNC_CALENDAR.equals(key)) {

Intent intent;

if (SettingsUtils.shouldSyncCalendar(getActivity())) {

// Add all calendar entries

intent = new Intent(ACTION_UPDATE_ALL_SESSIONS_CALENDAR);

} else {

// Remove all calendar entries

intent = new Intent(ACTION_CLEAR_ALL_SESSIONS_CALENDAR);

}

intent.setClass(getActivity(), SessionCalendarService.class);

getActivity().startService(intent);

}

}Let’s start writing our test for it:

@Test

public void onSharedPreferenceChangedRemovesSessions() throws Exception {

// Arrange

//Act

mSettingsFragment.onSharedPreferencesChanged(mMockSharedPreferences,

PREF_SYNC_CALENDAR);

//Assert

}As the test method name implies, we want to test that onSharedPreferencesChnaged removes the calendar sessions appropriately.2 We need to make sure the the else branch of the above if-else statement gets executed. To do that, we need to make sure that SettingsUtils.shouldSyncCalendar(getActivity()) returns false, but we can’t just go to the declaration of SettingsUtils.shouldSyncCalendar and change the code so that it returns false. We need to change behavior of our code without editing it “in place.”

Here’s the thing: because SettingsUtils.shouldSyncCalendar is a static method, we can’t actually do this. There is no seam for us to exploit here. If you code doesn’t have seams, you’re going to find it difficult to arrange in your tests.

Notice, moreover, that we can’t assert in this test either. How can we assert that an Android Service has been launched? There’s no straightforward way to do this, which is why the Intent class exists within espresso. What we need here is to be able to change the behavior of Context.startService so that it records that a service has been started, but we can’t. Obviously, we can’t edit the Context.startService method and we have no control over the Context returned by getActivity. We’ll see why that would create a seam later, but the important thing to note here is that if you code doesn’t have seams, you’re going to find it difficult to assert in your tests.

Suppose instead that the settings toggle code looked like this:

class CalendarUpdatingOnSharedPreferenceChangedListener {

void onPreferenceChanged(CalendarPreferences calendarPreferences,

String key) {

if (SettingsUtils.PREF_SYNC_CALENDAR.equals(key)) {

if (calendarPreferences.shouldSyncCalendar()) {

mSessUpdaterLauncher.launchAddAllSessionsUpdater();

} else {

mSessUpdaterLauncher.launchClearAllSessionsUpdate();

}

}

}

}Notice that we’ve replaced a static method call with an instance method call. Notice also that the details of how the SessionCalendarService is started is hidden behind a call to mSessUpdateerLauncher.launchClearAllSessionsUpdate(). These two changes let us arrange and assert in our unit test:

@Test

public void onPreferenceChangedClearedCalendar() throws Exception {

// Arrange

CUOSPCListener listener

= new CUOSPCListener(mSessionUpdateLauncher);

final CalendarPreferences calendarPreferences

= mock(CalendarPreferences.class);

when(calendarPreferences.shouldSyncCalendar()).thenReturn(false);

// Act

listener.onPreferenceChanged(calendarPreferences,

SettingsUtils.PREF_SYNC_CALENDAR);

// Assert

verify(mSessionUpdateLauncher).launchClearAllSessionsUpdate();

}The changes we made to our code gave us seams that we exploited in our unit test. Using mockito3, we changed the behavior of calendarPreferences.shouldSyncCalendar() so that it returns false without going to the declaration of CalendarPreferences.shouldSyncCalendar and editing it. We also used mockito to swap out a standard SessionUpdaterLauncher with an implementation that records that a particular method has been called. This, of course, is what allows us to assert in our test with verify.

The seams we’ve just created here are called “object seams,” and they’re something that I’ll cover more explicitly in my next post.

Conclusion

If you’re sold on testing, but you don’t understand what makes code testable, you can wind up trying to do the impossible: test untestable code. You may also wind up doing terrible things to your code base to try to add tests. You can avoid these situations by understanding what makes code testable. Testable code has seams, and without those seams, you’re going to find it difficult to arrange and/or assert in your tests.

Notes:

-

Thankfully, it looks like they may have fixed this in the 2016 version of the Google I/O app.

-

This behavior may actually be too trivial to test in real life, but its makes for a simple example.

-

Of course, using mockito to accomplish this isn’t absolutely necessary.