I concluded my last post by summing up what we’ve seen so far and what we still need to understand about RxJava:

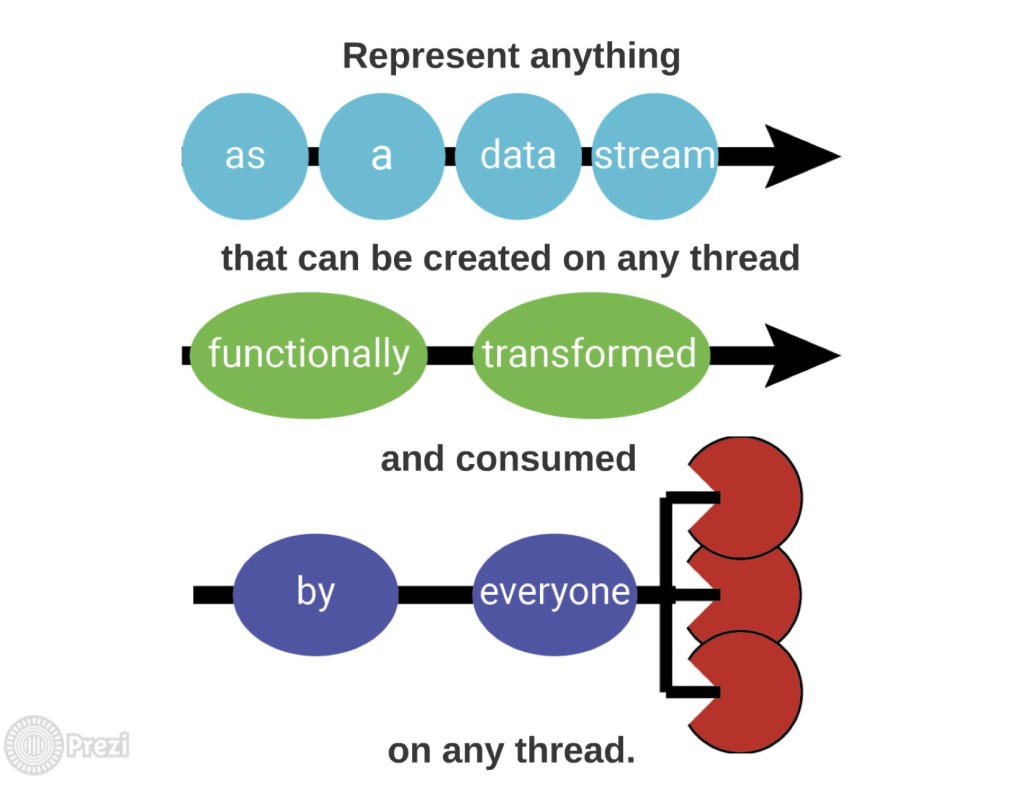

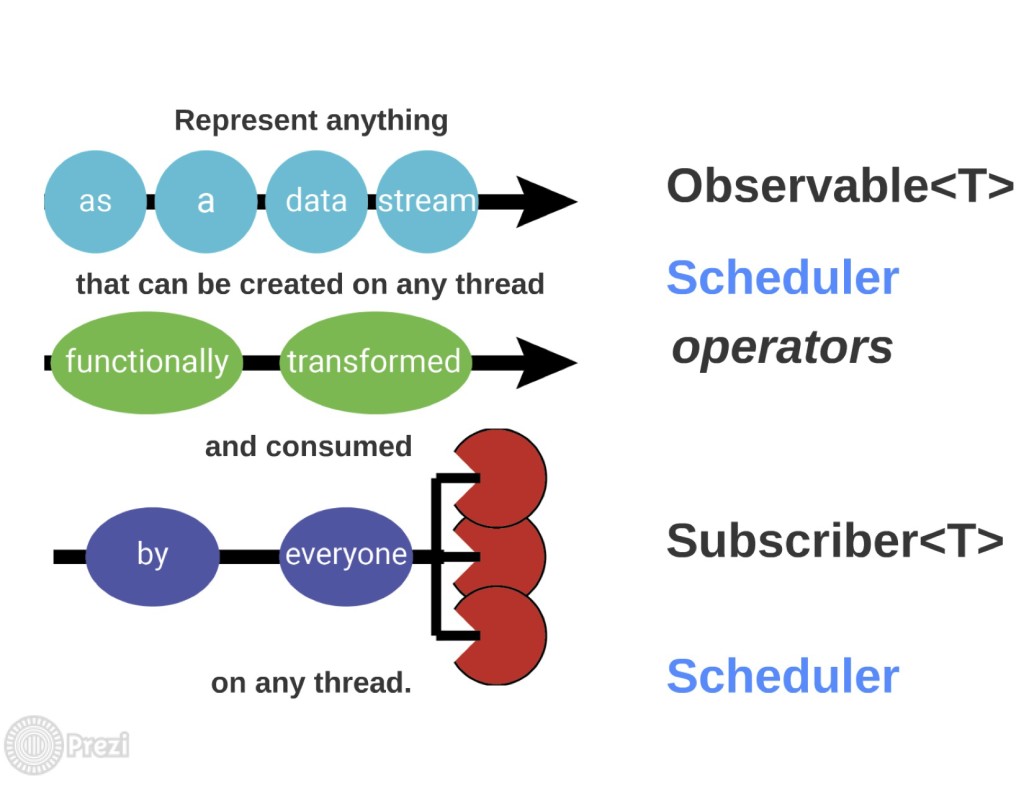

We now know what an asynchronous data stream is and we know that RxJava uses the Observer pattern to deliver these streams to everyone that’s interested. We still don’t know, however, what it means for a data stream to be “functionally transformed” nor do we know how RxJava allows us to represent anything as an asynchronous data stream that can be created and consumed on any thread. These are questions I’ll have to tackle in the second part of this written version of my upcoming RxJava talk.

In this post, I’ll fill in the missing gaps in our understanding of my initial statement of what RxJava allows us to do.

Recall that that initial statement was this:

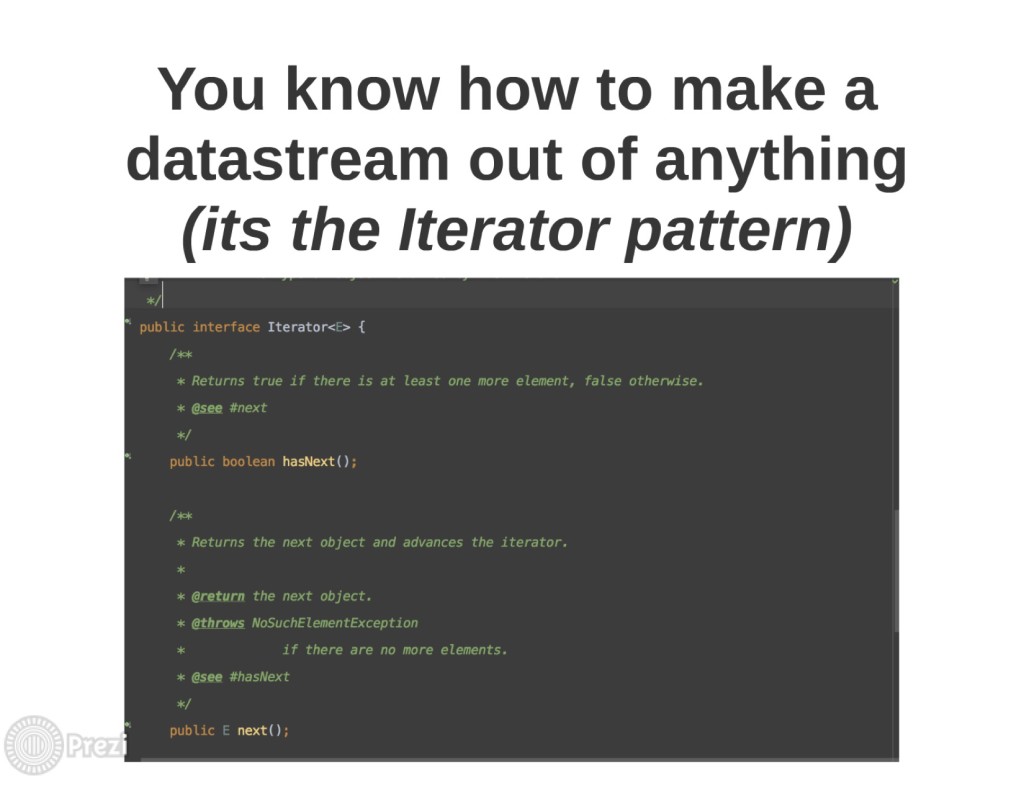

Recall that a data-stream, as I’ve defined it, is just sequential data that has a well-defined termination point and a way of notifying processors of that data that an error has occurred. RxJava lets us create asynchronous data streams out of anything. This might sound confusing until we remember that we are already familiar with a pattern that allows us to make synchronous data streams out of anything: the iterator pattern.

The definition for an Iterator looks like this:

Notice that an Iterator fits the definition of a data-stream. Its ordered data that can be processed by calling next(). It has a well-defined stopping point: when hasNext() returns false. Finally, processors of an iterator’s data can also be notified if there was an error processing the data: the iterator can simply throw an exception.

You can make any class iterable as long as that class can supply an iterator with which to traverse its elements. This makes it possible to turn any class into a synchronous data stream. This is actually how the for-each syntax works in java. All Collection classes can return an iterator that’s used to sequentially traverse the data they contain.

This shouldn’t be surprising since the motivation for the iterator pattern according to the Gang of Four is to:

Provide a way to access elements of an aggregate object sequentially without exposing its underlying implementation.-GoF, Design Patterns

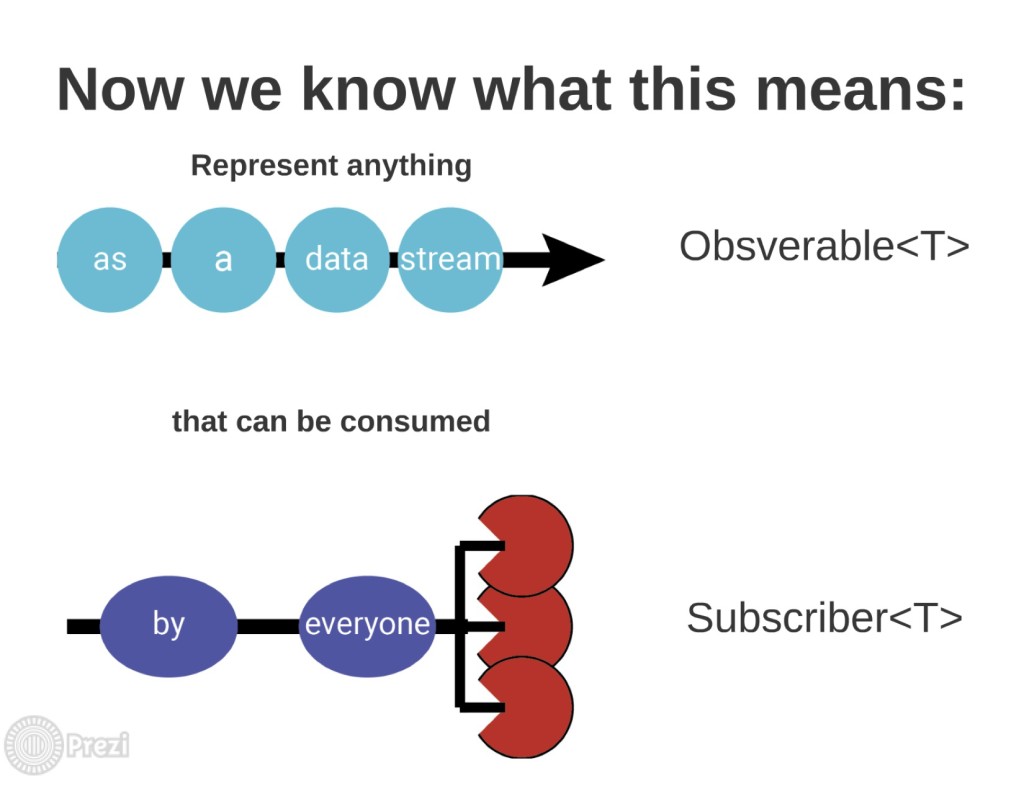

RxJava Observables can be created out of anything and remember that Observables are just asynchronous data streams. Because Observables are asynchronous data streams that can be created out of anything just as Iterators are synchronous datastreams that can be created out of (nearly) anything, the reactive x introduction refers to Observables as the “asynchronous/push dual to the synchronous/pull iterator.”

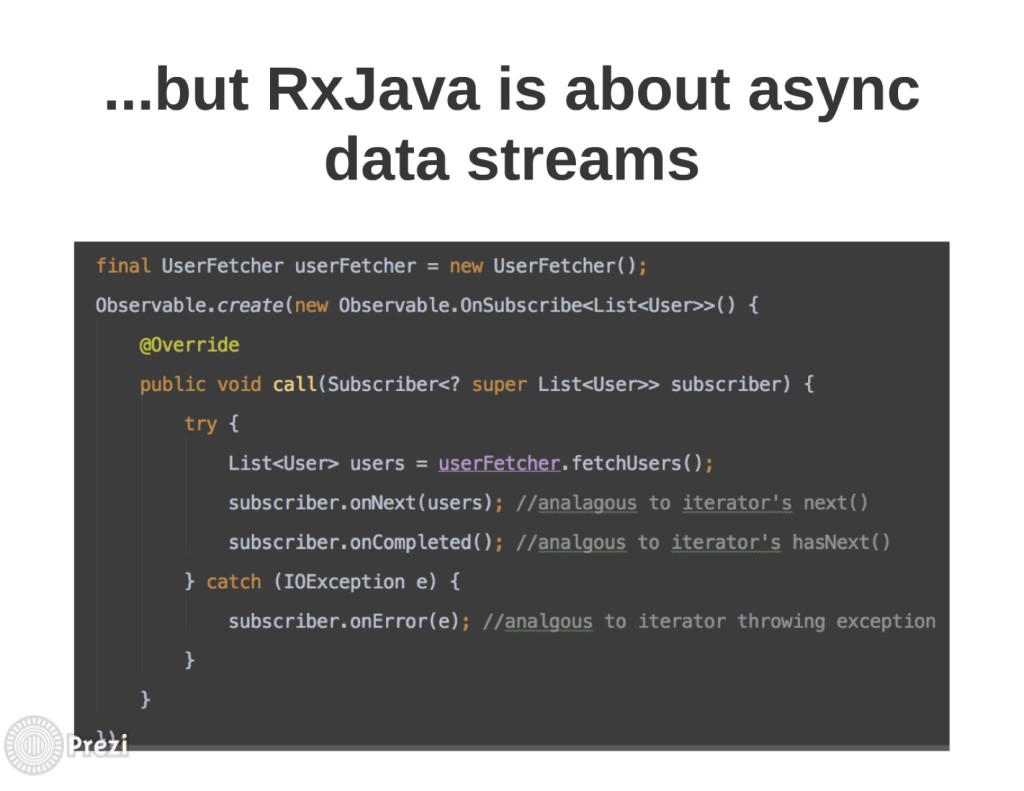

This will make more sense once we see what it looks like to create an Observable:

Here we’re creating an Observable that emits the data from a long-running operation performed by userFetcher.fetchUsers(). Once fetchUsers() returns with the Users, we call onNext() on the Subscriber that’s passed in to call() method. Recall that a Subscriber is just a consumer of asynchronous data, so by calling onNext(), we are passing the users we’ve fetched to the Subscriber. This call to onNext() as the asynchronous analog to the iterator’s next() method.

You’ll notice that there’s another call after onNext(): its the onComplete() call. This tells the Subscribers that the asynchronous data stream has reached its end. This call is the asynchronous analogue of the iterator’s hasNext() method returning false.

Finally, note that if there’s an exception thrown by the method that fetches the users, we call onError(). This, of course, is the asynchronous analog of the iterator throwing an exception while processing synchronous data.

Alright, so hopefully at this point, we know what this means:

But we still don’t know this:

When I say “functional transformation,” I’m using “functional” in the same sense that its used when people talk about functional programming. Functional transformations are transformations of data that don’t rely on any data outside of the function that does the transformation and that don’t have any side effects. We perform transformations of data all the time, but those transformations might not count as functional.

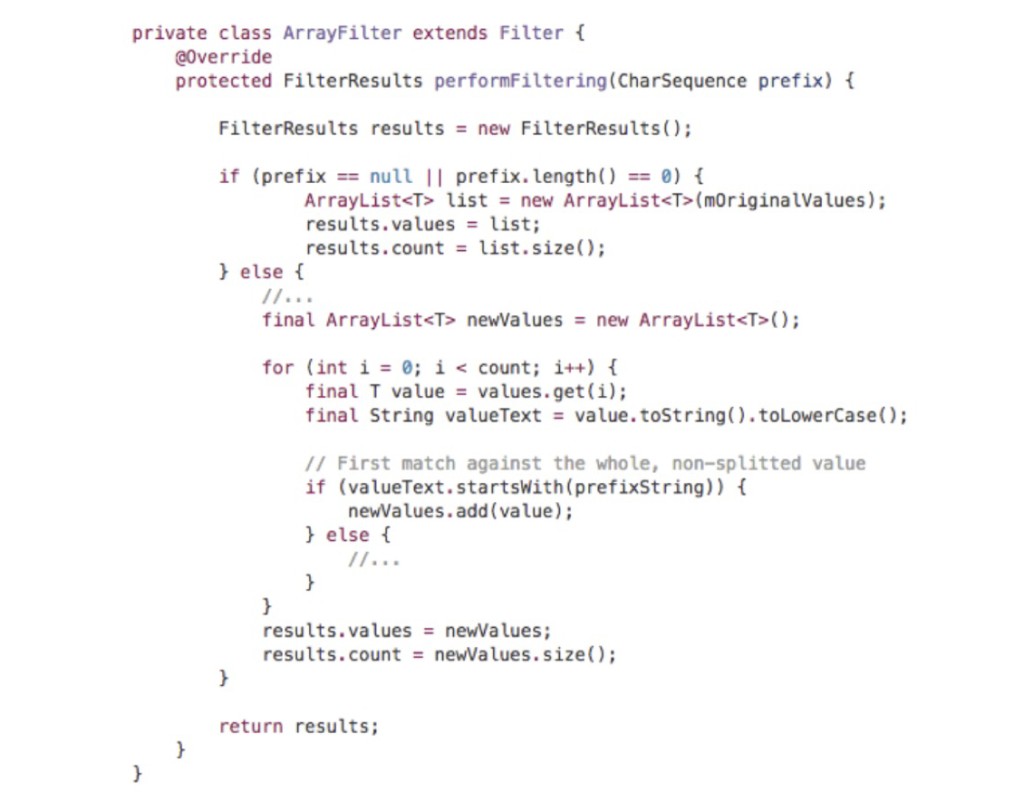

If you’ve ever written a filter for an list adapter, you’ve probably had to do a transformation of the unfiltered data. Here’s what this looks like in the Android Source’s implementation of filtering for the ArrayAdapter class:

This transformation, however, is not entirely functional. Its true that this method is creating a new Array to hold the filtered values rather than modifying the array of original values. This makes performFiltering() semi-functional since it doesn’t modify data outside of the method. However, because this method relies on data from outside of the function, it fails to be an entirely functional transformation of the unfiltered values.

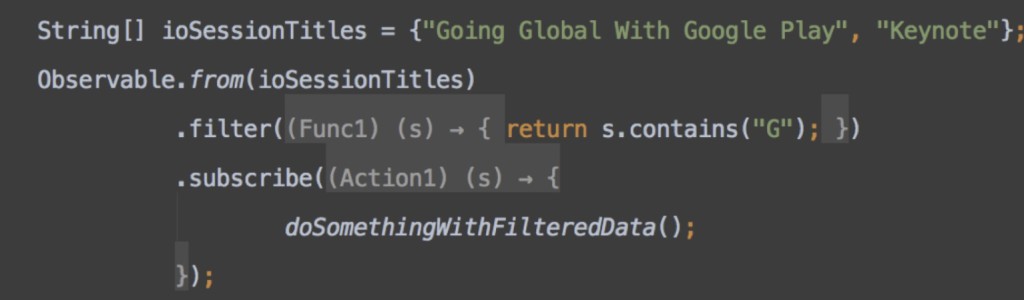

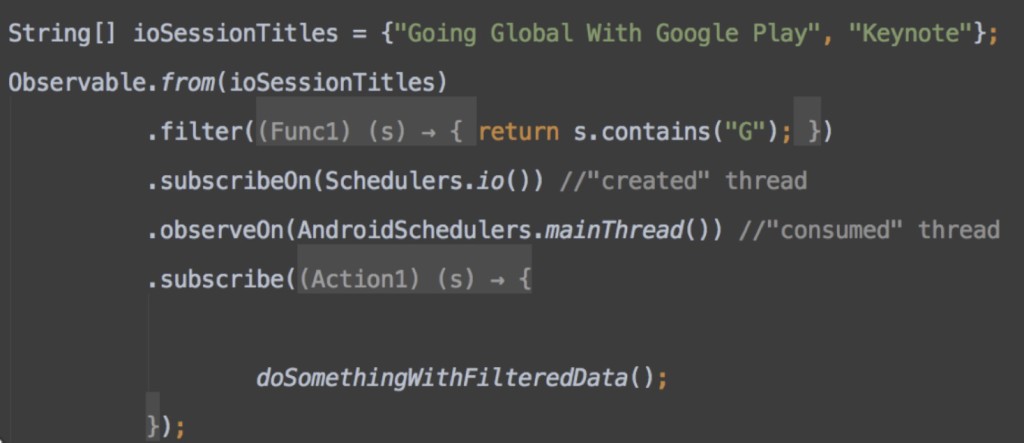

RxJava, on the other hand, does perform completely functional transformations of asynchronous data. Here’s what that looks like:

Here we’re creating an Observable out of an array. We then transform the data stream emitted by this Observable by calling filter() on the Observable created from the array. filter() takes a function that returns whether the items emitted by the source Observable should be included in the transformed data-stream. In this case, the function passed into filter() will return true for “Going Global with Google Play” and false for “Keynote,” so the former and not the latter will be emitted by the Observable returned by filter() and consumed by the Subscriber.

The filter call is a functional transformation because the original Observable that was created from the array is not modified and because the Func1 that performs the filtering operation does not operate on any data that exists outside of Func1.

These functional transformations are called “operators”, and their functional nature is what allows us to chain together multiple operators to shape the asynchronous data stream so that it can be conveniently consumed by a Subscriber. We’ll see what this chaining looks like later.

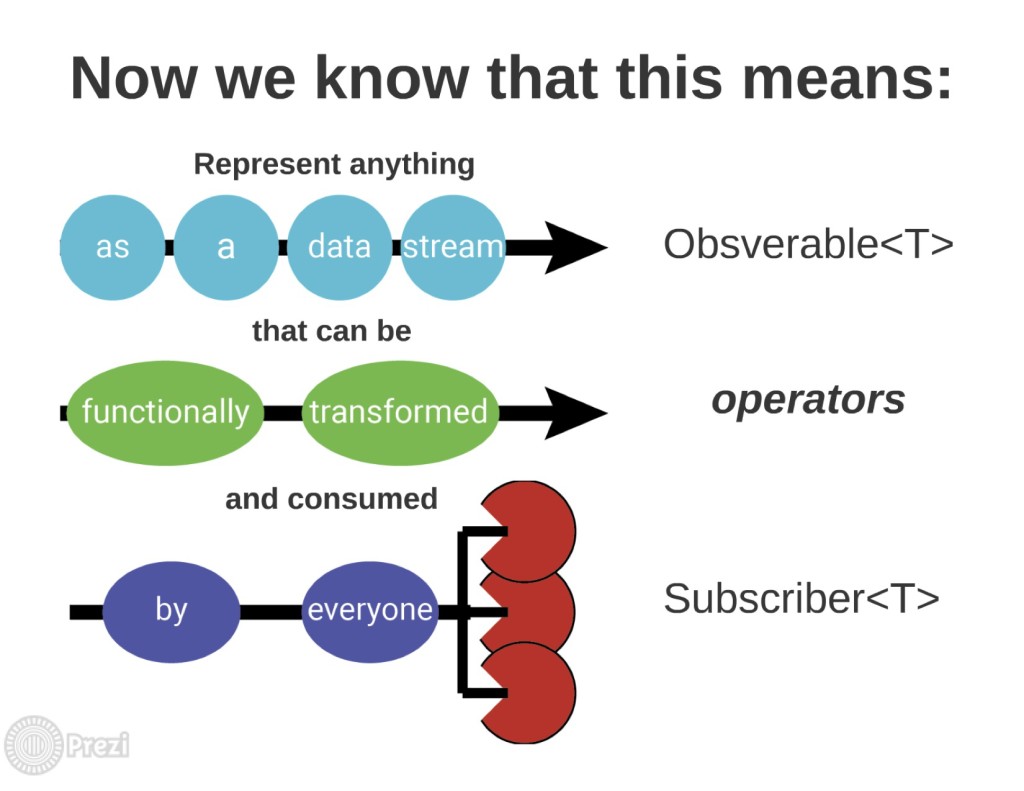

At this point, if I’ve done my job right, you should know that this means:

We still don’t know, however, how RxJava let’s us create and consume asynchronous data streams on any thread. This is accomplished through Schedulers and this is how Schedulers are applied to Observables and Subscribers.

The key lines here are the subscribeOn() and observeOn() lines. These lines take Schedulers that determine the threads on which asynchronous data is created and consumed, respectively. We pass a Scheduler to subscribeOn() that schedules the asynchronous data to be created on a background io thread and we pass a Scheduler to the observeOn() method that ensures that the asynchronous data is consumed on the main thread.

One quick thing to note here is that the AndroidSchedulers.mainThread() method is not actually a part of RxJava. Its a part of RxAndroid.

At this point, you should be in a pretty good position to understand all of my initial statement of what RxJava does:

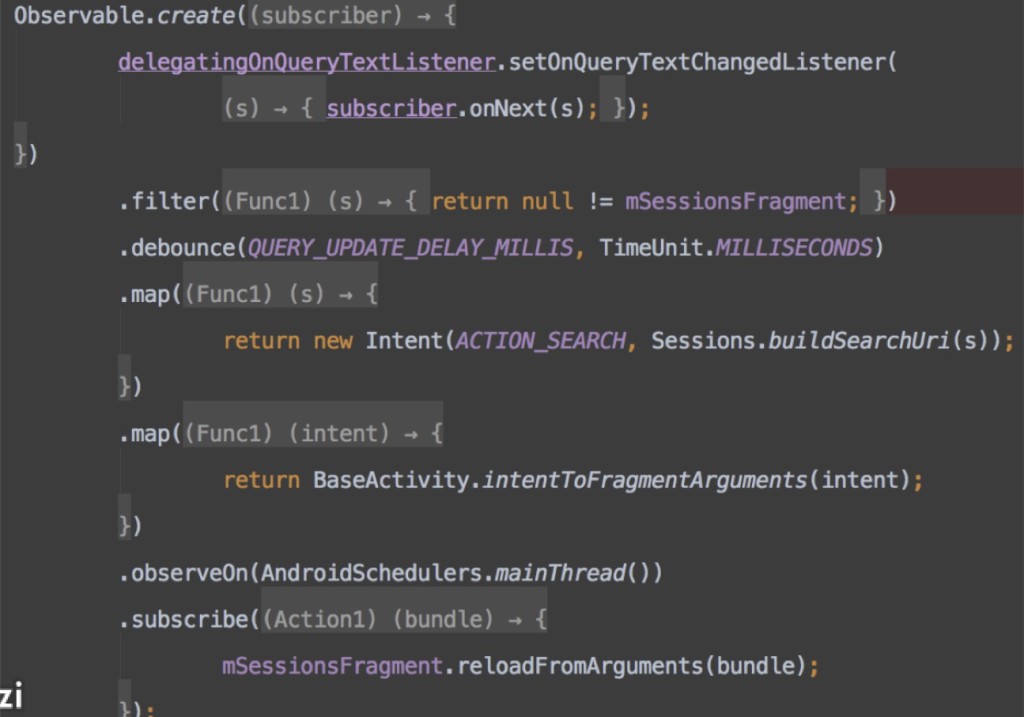

And now that you understand what RxJava is, you can understand how its able to make quick work of a task like the one I described in the first post in this series. Recall that the task was to execute a query from a SearchView within an Actionbar only if that query consisted of three characters and only if there was at least a 100 millisecond delay before any additional characters were typed into the SearchView.

This functionality exists already in Google’s iosched app. Here is a reimplementation of that functionality using RxJava:

I’m only going to explain parts of this snippet, but if you want to check out the full source, you can do that here.

Note that there are several operators here that I didn’t mention before, namely, debouce() and map(). RxJava has a ton of operators, so be sure to check them all out. The debounce() operator is what allows us to only execute a search on a query only if there’s been a 100 millisecond delay after the last text change in the query string.

The filter() operator here is only used to make sure that there is a fragment available to display the data fetched from the search, but we could have easily added another filter() operator that would check the length of the query string.

The map() operators transform the data emitted by their source Observable. The first map() operator converts the query string into an intent created from that query string. The second map() operator converts that intent into a Bundle that can be used by the SessionsFragment to load the appropriate sessions (based on the original query string).

If I’ve done my job right, hopefully now you know what RxJava is and why its awesome! Feel free to point out anything that was unclear or inaccurate.